Reupholstering a Chair with Overshot Fabric

By Melissa Ludden Hankens

After returning from a fabulous time at the New England Weavers Seminar in July, I found myself rewriting the beginning of this article. I was so lucky to spend two days in a round-robin style class taught by Marjie Thompson entitled 18th & 19th Century High Fashion for the Middle Class. To say that Marjie knows an extraordinary amount about historic textiles seems to be an understatement. Oh, to have an hour swimming about in her brain!

There were ten of us in the class, and we rotated, weaving a new sample at each loom. Marjie shared her knowledge of the patterns we sampled, and I came away with an even greater interest in this subject in addition to a binder filled with samples. There really is no greater way to learn than a hands-on workshop. I am already preparing to wind a warp for a dimity project. I’ll keep you posted on my progress.

One interesting piece of information I learned is that overshot is a fairly modern term. Originally this type of weaving would have been referred to as floats or floatwork. It seems that many people are returning to this original terminology, though the weaving world has thus far shown little interest in making the change back. Personally, I like it. Floatwork sounds a bit less frenetic than overshot – as though I’m peacefully hitting my mark rather than missing it in a wild fashion.

Until recently, my floatwork experience was limited to one project. This was created using Cascade 220 back in April 2008. The pattern is Leaves on p. 118 of The Handweaver’s Pattern Directory by Anne Dixon. I was criticized for having floats that were too long and would easily snag, but I loved my fabric. I turned it into a little tote that fit perfectly into my bike basket and never experienced a snag. Thankfully I took a photo back then, as the bag is currently in storage and missing the bike paths of Boulder.

When I first considered writing this article, I wasn’t confident enough with my weaving vocabulary to write something that a true beginner might actually understand. The information out there assumed, and still assumes, a certain level of weaving knowledge. I learn best by seeing something demonstrated, not by trying to translate written instructions. So how does one write an article for people like me? Let’s start with some basic terminology.

What Is Overshot/Floatwork?

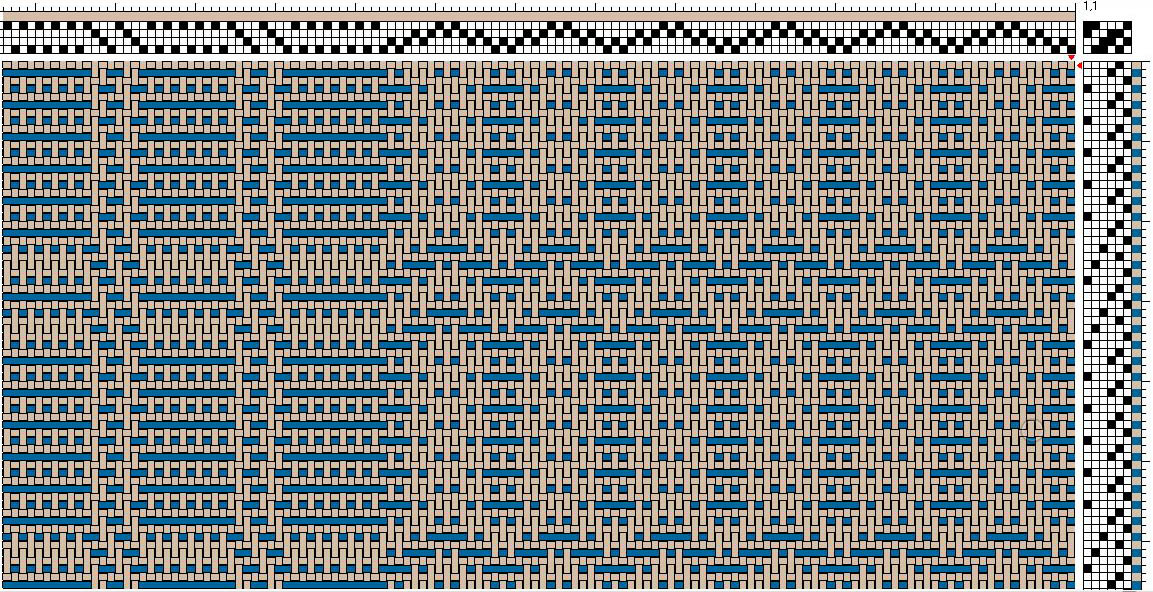

Floatwork, formerly known as overshot which was originally known as floatwork, is a block design traditionally woven on four shafts where a heavier pattern yarn floats above a plain weave ground cloth and creates a raised pattern. Your plain weave background cloth is woven using a finer yarn in your warp and in every other weft pick (these weft picks being the ‘use tabby’ part of your pattern.)

This finer yarn is hidden in places by the thicker yarn floats, blended in places with the thicker yarn (as plain weave) creating areas that are shaded (referred to as halftone), and woven across itself to create delicate areas of plain weave. Most of us think of antique coverlets when we hear ‘overshot.’

What Is Tabby?

For some reason the term tabby has always annoyed me. It made me think of cats (I’ve got two – one of whom decided to take my seat when I got up to get a quick snack – and I love them both dearly) not weaving until I looked up the origin of the word on etymonline.com.

What a lovely history. I like ‘tabis’ (pronounced as tabby, but with a bit of French flair). It adds a bit of je ne sais quoi to your weaving, non?

Back to business. Tabby is a plain weave pick that anchors your pattern pick in place. When weaving floatwork, every other weft pick is tabby. Your pattern pick needs the tabby pick to stabilize the cloth and keep the pattern picks from becoming distorted. This also means that you are working with two shuttles, one holding your tabby yarn and one holding your pattern yarn. This two-shuttle thing can be a bit awward at first, but you’ll get the hang of it with a little practice.

What Is a Block?

Initially, the concept of a block was the toughest one for me to grasp because I was looking at the pattern as a complete unit rather than a combination of units. The block is simply a unit or part of a particular pattern in the shape of a rectangle or a square. There are usually at least four threads in a block, two pattern and two tabby. So you treadle the same pattern pick two or more times in sequence (alternating with your anchoring tabby picks) to create a solid shape in your pattern. Think about coloring in graph paper. If you color in four squares in a row, it just looks like a thick line, right?

But if you color in four squares in a row directly on top of the first four squares to create an eight square rectangle, suddenly you have something that stands out on the page. This is your block, and of course it can be some number of threads wider and longer to create various shapes. Keep in mind how you plan to use your fabric and plan your blocks accordingly. In other words, manage your float length.

It’s Twilling

Here is the thing about floatwork that really helped it to make sense for me. It is basically a twill weave. As Mary Black puts it, “An examination of an overshot draft shows it to be made up of a repetitive sequence of the 1 and 2, 2 and 3, 3 and 4, and 4 and 1 twill blocks”.

Let’s look at the pattern picks only. When weaving, your pattern blocks should overlap by one thread. This creates a pattern that flows from unit to unit instead of making a sharp step. It also means that the last thread of a given block is the first thread of the next block, and as you are initially threading your loom, your threads will move from odd shaft to even shaft.

Choosing the Right Yarns

Choosing yarns to weave floatwork can be challenging. Generally speaking you want your pattern yarn to be about twice the diameter, or grist, of your tabby/warp yarn. Your tabby yarn and your warp yarn are generally the same yarn. I say generally because I can see so many non-traditional ways to weave floatwork that involve breaking the rules. Imagine, for example, taking a small part of a given pattern and blowing it up to a massive scale to do a wall hanging or using three different yarns to create a completely different visual experience!

When choosing your yarns, you can always search online to see what other folks have used successfully. Ravelry.com, Weavolution.com and Weavezine.com are all good places to start. You could also double your tabby yarn to create a pattern yarn. I did this with my bike basket, using a different colorway to create the contrast. And of course there is our friend the sample. Pick a warp and experiment with your weft.

Treadling

When treadling a block pattern with tabby picks, I find it helpful to tie my tabby treadles on one side and my pattern treadles on the other. This way you can dance back and forth from left to right as the treadling sequence is always going to be pattern-tabby-pattern-tabby. It feels more like walking or pedaling a bicycle to alternate in this manner.

Probably the trickier part of treadling is keeping track of where you are in the sequence. Like many traditional floatwork patterns, the pattern I used is meant to be woven tromp as writ or as drawn in. This means that your treadling is the same as your threading. So if your threading is 1-2-1-2-3-2-3-4, then your pattern picks are treadled 1-2-1-2-3-2-3-4. You will be throwing tabby picks after each pattern pick, so your actual treadling looks like (in this example let’s consider your tabby picks to be ‘a’ and ‘b’) 1-a-2-b-1-a-2-b-3-a-2-b-3-a-4-b. If this looks a bit intimidating, don’t fret. At first it might feel that way, but the pattern really does start to make sense after you get going.

In the case of my draft, the threading sequence is 134 threads long. This is a lot to remember, but I used an index card to write out the sequence. I marked my place by sliding a second card down the pattern as I progressed, keeping it in place with a paperclip.

Throwing Two Shuttles

Here is a brief video by Laura Fry, the Queen of Proper Weaving Technique, on how to throw two shuttles.

It is most helpful not to wind too much of your cloth onto the cloth beam when advancing your warp so that you have a little shelf to hold the shuttle not in use.

Project Specs

Weave structure: overshot (floatwork)

Finished size: before washing, 21-7/8" x 106"; after washing 21" x 99"

Warp length: 4 yds

Number of warp ends: 564

Width in reed: 23.5"

EPI: 24

What You'll Need

-

Warp and tabby weft: Foxfibre 10/2 organic unmercerized cotton in 50% green

-

Pattern Weft: JaggerSpun Maine Line 2/8 wool in peacock

-

4-shaft loom with at least 24” weaving width

-

two shuttles

Directions

I used a pattern from Mary Meigs Atwater’s Shuttle-Craft book listed in the Resources section. The draft is No. 18 Name Unknown and is on various pages depending on which printing of the book you have. You can find it listed in the chapter or sub-chapter entitled ‘Notes on the Overshot Drafts.’ As someone who generally cheers on the underdog, I was drawn to this pattern without a name.

Atwater’s patterns are written for a sinking shed loom. For a rising shed loom, like the Baby Wolf I used, simply tie up the shafts left blank in the draft instead of the shafts she tells you to tie up. For all of her traditional floatwork patterns, including the pattern I used, this tie-up would be 3-4, 1-4, 1-2, 2-3. Your tabby tie up should be 1-3 and 2-4.

No. 18 Name Unknown is woven tromp as writ, as I mentioned earlier. Weave it in the order it’s threaded, alternating each pattern pick with a tabby pick. Your pattern shuttle will hold the thicker yarn and your tabby shuttle will hold the finer yarn that was also used in your warp.

I washed this in my front-loading washing machine on the wool setting and air-dried it on the clothesline. There was a note in the book that No. 18 Name Unknown, and its friend No. 17, are “plain patterns and suitable for couch covers or the coverlet for a man’s room, rather than for more frivolous purposes”. Perfect. I’m not much for frivolous, and I had been looking for the perfect fabric to re-cover an old chair.

I tried my hand at a bit of reupholstering, and am quite pleased with the results. And now to find a way to keep the cats from having their way with it.

Notes

Here is a list of books and magazines that might be of interest if you’d like to learn more about floatwork/overshot. Many of these references include patterns in addition to thorough instructions.

Atwater, Mary Meigs. The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Handweaving. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1928. Just scored a first edition on ebay for $9! I now have three copies and am seriously in love with this book (taken with a grain of salt as she is rather traditional.)

Black, Mary E. The Key to Weaving. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980.

Bress, Helene. The Weaving Book. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Flower Valley Press, 2009.

Patrick, Jane. “ ‘Country’ Overshot.” Handwoven September/October 1985: 48 – 51. Print.

Pettigrew, Dale. “Weaving with Tabby.” Handwoven November/December 1982: 62 – 64. Print.

If you can find this issue anywhere, I’d recommend picking it up. It’s full of great information on historic weaving, but also has a super article on understanding and writing drafts by Debbie Redding (aka Deborah Chandler).

If you have a particular interest in old coverlets, Eliza Calvert Hall’s A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets and The Coverlet Book by Helene Bress are both interesting resources, the later being particularly thorough. I can only imagine the time and research that went into this pair of tomes. And if you are simply looking for patterns, The Handweaver’s Pattern Book by Marguerite Porter Davison and The Handweaver’s Pattern Directory by Anne Dixon are just for you.