Today we want to highlight textile good works around the globe that you can help support through your purchase of hand-crafted products. We’re including a link to the WARP Artisan Textile Resources: Your Guide to Global Handmade Textiles. Reading through the Guide you’ll find heartwarming stories about projects worldwide, along with many dedicated folks helping support traditional textile making in parts of the world where handcrafting goods is a means of supporting families—as well as maintaining age-old textile traditions that we here at Schacht are passionate about the importance of helping to sustain.

Mayan Hands is one of the featured groups highlighted in the Guide and is a textile community that we help support with our Cricket Bag, designed especially for our Cricket Loom. It all came about several years ago when Deborah Chandler, then the director/president of Mayan Hands in Guatemala, was visiting us here in Boulder, Colorado and mentioned that her weavers needed more outlets for their products. At the same time we were looking for a sturdy bag for our Cricket Loom. As a way to support the weavers, we commissioned Mayan Hands to weave bags for us, which are then sewn by another woman/group in Guatemala before shipping to the US. These bags are offered in several traditional colors and patterns. The weavers and sewers are paid a fair trade wage and their purchase truly makes a difference in sustaining the weavers’ families and their traditional way of life.

I asked Deborah to write a piece about some of the weavers of Mayan Hands so that we can know them better and the impact weaving makes on their lives. This story of Mayan Hands is similar to the other stories you’ll read in the Artisan Textile Resources Guide. - Jane Patrick

Mayan Hands and The Story of the Cricket Bag

Looking at the finances of a typical Mayan family, it can be understood how important weaving is to their family income. For example, a Mayan family consumes about two pounds of corn per person per day. So a family of six needs 12 lb/day or 84 lb/week or 4,368 lb/year. Maria Ana Lajuj and her husband Paolino Sarpec and their four children are blessed to have their own cornfield, which in a good year produces enough to feed the family. But 2014 was not a good year. A wide-spread drought killed almost the entire corn crop in the “Dry Corridor” of Guatemala, which means that at the current price of $.24/pound, it would cost a family like Maria Ana’s and Paolino’s $1,048.00 for their most basic staple. To put that in perspective, at minimum wage, working full time, it would take three months to earn enough to buy that much corn.

In the 1980s the country of Guatemala was in the throes of an internal conflict that affected every person in the country. During that decade Guatemalan anthropologist Brenda Rosenbaum lived with different communities of Mayan women while conducting her field work. She was profoundly impressed with the strength and beauty of the women, including and especially their attachment to weaving on the backstrap loom, an important part of Mayan life that has been passed down from mother to daughter for thousands of years.

Equally profound was the awareness of the difficult lives the women faced, from both the “Time of the Violence” and staggering poverty. Combining Brenda’s heart with the business skills of Brenda’s husband, Fredy, the couple founded Mayan Hands, a fair trade organization that for a quarter of a century has provided Mayan women with a way to earn a living with their greatest skill – weaving.

With the passage of time Mayan Hands has branched out and groups now include basket makers, felters, crocheters, embroiderers – and foot loom weavers. Since 1996 Mayan Hands has worked with the group Flor de Algodón – Cotton Flower – in Chuaperol, Rabinal. The women started out in life as backstrap weavers, then as adults learned how to weave on much faster and therefore more lucrative foot looms. In many cases, once the women learned, they taught their husbands, and now couples work as teams in their own homes. One big advantage of working at home is that it makes caring for children much easier. While many of the families also have parcels of land and/or other lesser sources of income, as a “steady job”, weaving is their best option for earning a living – at least as long as they have a fair trade client like Mayan Hands. Selling locally is a climate of fierce competition. Of the 15 million people who live in Guatemala, more than 40% are indigenous Maya. Of these, more than half a million are weavers.

Flor de Algodón, Cotton Flower, a group of foot loom weavers

Maria Ana is the leader of Flor de Algodón, Cotton Flower, a group of foot loom weavers in the village of Chuaperol, outside of Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. As a child Maria Ana traveled with her family as migrant workers within Guatemala, picking cotton and other crops. Even so, she learned to weave on a backstrap loom, as did most Mayan girls. Maria Ana is smart and a hard worker, and as an adult she became a public health promoter, traveling to small villages throughout the area. Then the opportunity came to learn to weave on foot looms through a program sponsored by the Center for Integrated Families in Rabinal. Maria Ana jumped at the chance. In time she founded Flor de Algodón and has been weaving ever since.

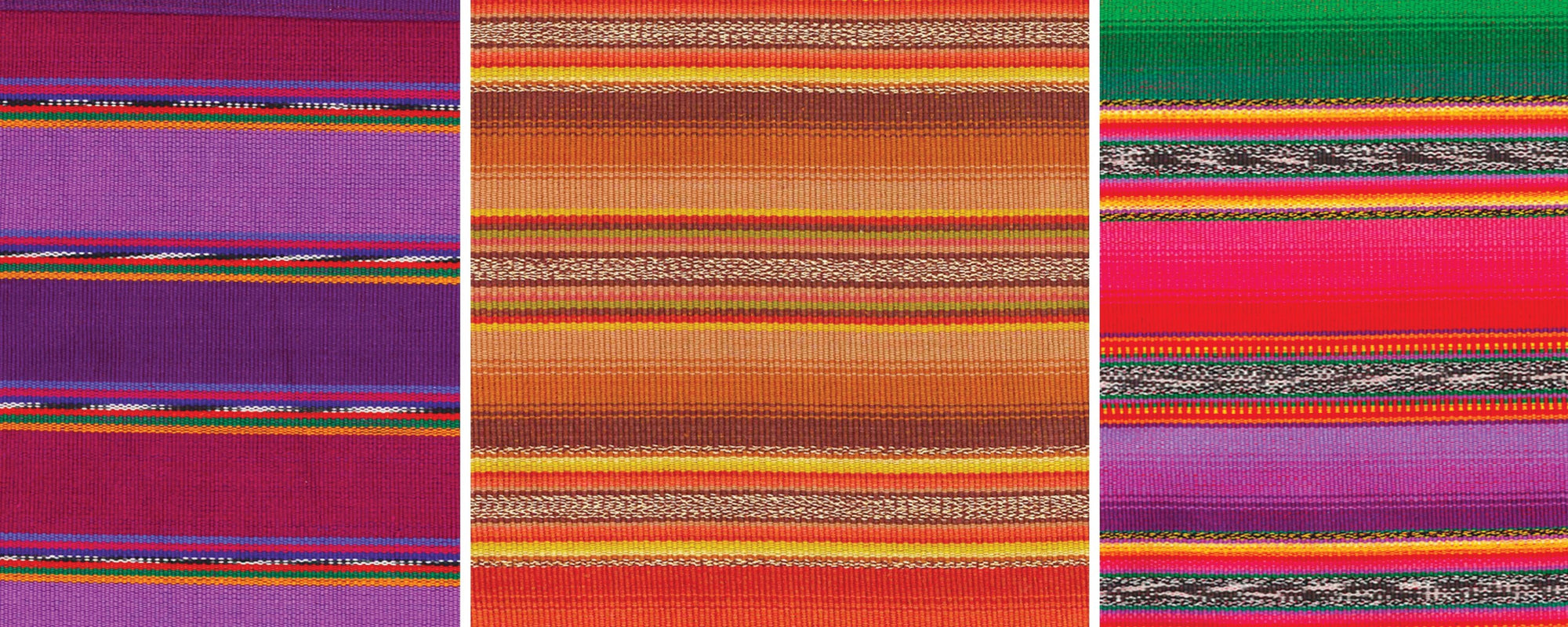

The worldwide economic crash that began in 2008 had a big impact on the group. In an effort to keep the group working, Mayan Hands has designed new products made from the same cloth: leather-edged shoulder bags, assorted pouches for electronic devices, notebook covers, and smaller pieces like coin purses and coasters. The structure of the cloth itself stays constant; what changes are the colors, for which Guatemala is famous among the textile cultures – and tourist destinations – of the world. In Guatemala, it begins and ends with color. The family histories of the women and men of Flor de Algodón are tales of being migrant workers within Guatemala, losing too many family members to violence, lack of education, droughts that kill off crops, the pain of watching children suffer with terrible health problems, and the circumstances of daily living that drag people down. But their stories also include tremendous resilience, hard work, strong families, a determination that their children’s lives will be better, and a deep faith that the seemingly impossible is in fact possible.

To learn more about Mayan Hands visit www.mayanhands.org