By Jane Patrick

There are few who have contributed so much to our knowledge of handweaving. We have Peter Collingwood to thank for his inquisitive mind, his thorough explorations of textiles, his tenacity in following a thread to discover a fabric’s structure, and his desire to write it all down. Hearing that he had passed away on October 9th while working in his studio seemed a fitting end for a man who’d spent his life in textile pursuits. Though he is no longer with us in person, his books and rugs, spit-ply baskets and macrogauzes, live on. In 1987, as editor of Handwoven magazine, I had an opportunity to interview Peter Collingwood. Below is what appeared in the September-October 1988 issue.

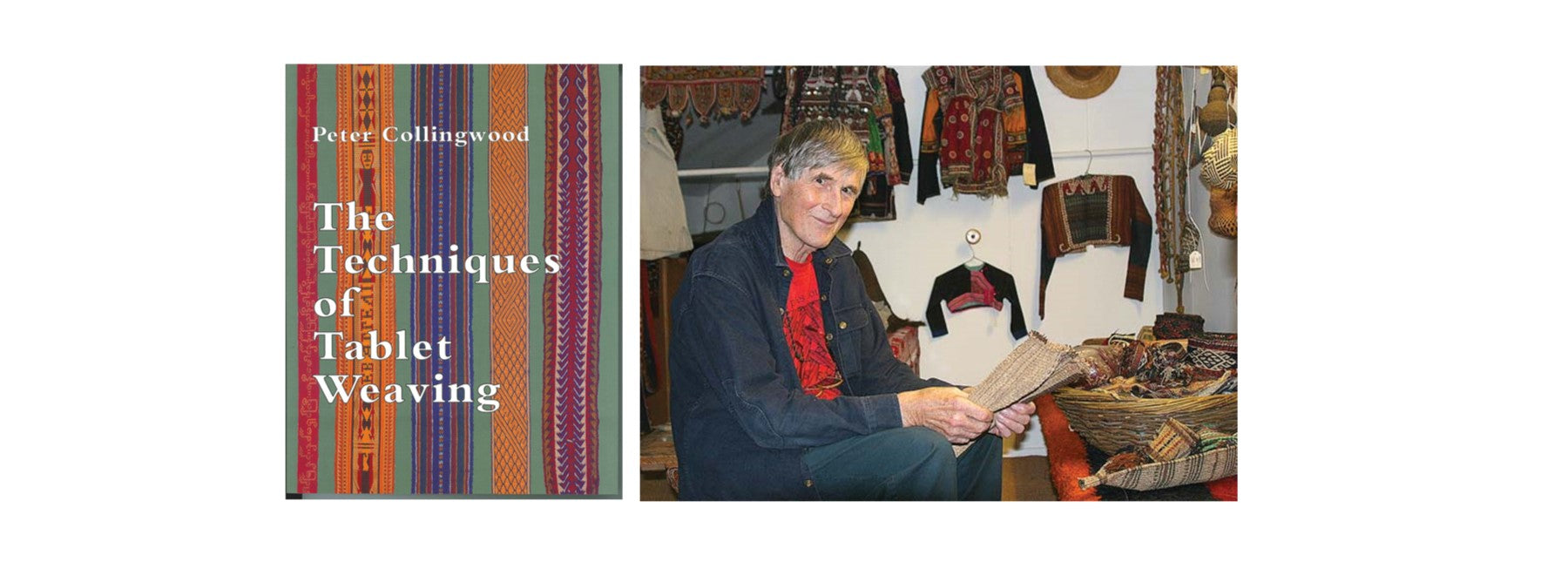

Introduction: It is a rare weaver who has not heard of Peter Collingwood. He is renowned as a rug weaver; his book The Techniques of Rug Weaving, published in 1968 and now in its ninth printing, is considered the definitive reference on the subject. Shaft-switching, a Collingwood invention which has become universally accepted is his trademark. Exhibitions of his work often include is “macrogauzes”, hangings which feature twisted and crossed threads in artistically intricate patterns, created with yet another loom adaptation he developed. He may be the foremost authority on sprang and card weaving, subject of two additional books he has written. You might expect Peter Collingwood to have a physical stature and (justifiably) an ego to match is legendary world-wide reputation. It comes as a bit of a surprise, therefore, to meet this quiet, unassuming man for the first time. He is not a showman. He does not need to be; his work speaks for itself. He is a modest, soft-spoken man with a clever, subtle sense of humor. Interweave Press was fortunate to have the opportunity to talk with Peter during his 1987 teaching tour of the U.S., and we are pleased to present that interview here.

IP: Everyone knows who Peter Collingwood is. You’ve put in 35 years and during this time you’ve been a tremendous influence on the weaving world. You’re not only weaving, you’re teaching, writing and collecting textiles. I’d like for you to talk about how you’ve come to do all these things.

Peter Collingwood: It began by giving up being a doctor, which I didn’t like. As a child I was always confident in the way that I could do things with my hands. My favorite game was to balance a stick on my fingers and toss it up in the air and catch it balancing it again. I was interested in skills and I always felt confident that I could construct toys or make things. I certainly wasn’t confident in curing people of the diseases they presented. So, when I came across a loom in an occupational therapy department of a hospital, it interested me as a purely technical device. At the time, I knew absolutely nothing about weaving; all I saw was a machine. I made myself a very simple sort of inkle loom and added a pedal for making the sheds. I then put two inkle looms face to face so that I could weave wider fabrics. Then I added four shafts. For me, learning to weave was just finding things out for myself because at that stage I didn’t have any books on weaving. I can remember puzzling over a houndstooth jacket fabric and thinking that this must take three harnesses to weave, which was completely wrong. Finding out for myself that this weave required four harnesses was much more important for me than if I had read it in a book.

IP: Were you a doctor at that time?

Peter Collingwood: Yes. I was doing my internship at the time, and then after that I had to do two years in the army which gave me a lot of weaving time. I built a portable loom and I would whiz around in an army ambulance with this loom in the back on which I wove scarves furiously. When I left the army I saw an advertisement to work in the Red Cross in Jordan with Arab refugees. I thought that this sounded worthwhile, so I went there for nine months. This is when I came across ethnic weaving for the first time. When I returned to England, I bought a loom from George Maxwell and when I went to visit him he suggested that I visit Ethel Mairet who was the most important weaver at the time and lived close to him. I asked her if I could work with her, and I think she was a bit intrigued because she’d never had a man work in her workshop before. She said that I could come for a month, and I sort of bumbled my way through. I’d never thrown a shuttle; up until this time, I’d just poked little sticks through the shed. But Ethel Mairet had proper looms with shuttles and pedals. For me, it was a very strange experience, but it was an eye-opener because it was the first time I had met somebody who you’d now say was weaving art fabrics. She had an aesthetic approach to weaving and she wasn’t just mechanically throwing shuttles and beating up the weft. Ethel Mairet had a very good eye for color, texture and quality. Just to spend time in her house was an education, as there were textiles every where, some collected on her trips on the continent some from the great French designer, Paul Rodier. By the time I left Ethel Mairet’s workshop I had met other people, and I started weaving rugs with Barbara Sawyer, one of the people I’d met there. She did the designing and I did most of the weaving. I think we quarreled about something, and then she passed me on to Alastair Morton who was perhaps the most important person I worked with because he had a very technical approach that was more allied to the way I tend to look at things. Alastair would plan a long sample warp and ask me to see what I could get out of it. Then he would just leave me to work, which was wonderful. At the time I didn’t realize how much he was allowing me to do. After the sample was finished, he would pore over it inch by inch, and then ask me to weave ten yards or so of some little bit of it. He was very good at designing what I call a “pregnant” warp, one full of possibilities. This is when I started weaving multi-shaft rugs. Alastair had done single corduroy, and then I thought of the double corduroy idea. By this time I’d made a funny little eight harness loom which had keys like a piano, one for each harness. It was something like a dobby but you selected your harnesses for each shed rather than having them pre-selected. It was quite good for designing and I worked out a lot of multi-shaft pieces on it, including a block weave which Alastair let me weave in his workshop. I then moved to London and set up a workshop to weave rugs in a little room behind a furniture-moving firm. That was in 1953.

IP: Was it your intention at the time to make weaving your career?

Peter Collingwood: Yes, I was certainly determined to try it, especially as I was repeatedly told it was impossible. I knew I had to make a rug in two days so that I could sell it to a shop for about four pounds (which was something like $7.50). I could make a rug in two days if I limited myself to shuttle-thrown designs, and loom-controlled patterns. I abandoned traditional ways of making rugs because I needed the speed to survive. The most important thing to me was not to be a failure at weaving. What I mean by traditional techniques are tapestry, soumak, knotting—the ways in which rugs have been made in the past that are very slow but which give limitless design possibilities. When designing, I never start with a blank sheet of paper and some wonderfully inspired design and then ask how can I weave it? Rather, I always start with a technique, do the long sample and see what the technique will produce. I try to exploit what a technique will give me rather than impose a design on a technique. If a technique automatically gives little square blocks, then I try to see what can be done with little square blocks. If a weave automatically gives diagonal lines, then I see what I can do with diagonal lines. It’s one of many approaches, but it’s the only way I know how to do things. It’s important to be as critical of your work as you are of, say, modern furniture or painting. Try to apply the same standards you apply to other things to your work. I find design the most difficult part in weaving; especially trying to think of ideas that are new. I feel the only thing that can help you in designing is your own eyes—and your eyes need to be educated in some way. Mine, I hope, have been educated by the things I have around the house, objects I’ve collected: textiles, baskets, wooden pieces, pottery. Their shapes, colors and textures are constantly teaching my eyes lessons in design. My first rugs were very simple, mostly woven in summer and winter which I thought I’d invented until I found it in a book. However, it wasn’t until I got into shaft-switching that I had to seriously think about designing because before that, everything was pretty simple. With shaft-switching I realized that I could make any shape. Now I wasn’t just limited to squares and rectangles. Shaft-switching meant that I could get away from straight-sided motifs. Designing is difficult. We’re not living in a tradition, are we? Today anything is possible, whereas in the past, the tradition you lived in determined, in part, your designs. For example, if you made knotted rugs and lived in Afghanistan in 1850, you couldn’t make just any sort of knotted rug; you could only make a knotted rug that was like the one your father made, in the colors that were local to your tribe. Since we don’t have this kind of tradition now, I’ve relied on technique to limit my designs. For example, even with all its possibilities, shaft-switching has its limitations: you can only use two colors at one time, and you can’t make swirling, curvy designs. Designing macrogauzes, of course, is something totally different because it’s a much freer technique. With pieces such as these that hang on the wall, you don’t have the practical limitations found in rug weaving. Structurally, macrogauzes only need to hold together enough so as not to actually fall to pieces when you hang them on the wall. Because it’s possible to do so many different things with the macrogauzes, I find I need to limit myself. I decided before I start a piece, for example, that I’m going to just cross threads over on this piece or only twist threads. Otherwise things just get out of hand.

IP: Part of what you do is creative work, but the bulk of your time is spent in production. How do you do it?

Peter Collingwood: I’d say that I’m inventive, rather than creative. And I am inventive so that I can continue to be a production weaver. I think these things are important. There’s no point in trying to be a handweaver and just doing what a machine can do. To justify myself as a handweaver, I feel that I have to be able to do something a machine can’t. This certainly applies to macrogauzes because there’s not a machine that can make them; maybe it doesn’t apply to shaft-switching because I suppose that if there were enough people who wanted shaft-switched rugs, someone would invent a machine to make them.

IP: How does writing fit into what you do?

Peter Collingwood: I spend most of my time weaving. But when I wrote The Techniques of Rug Weaving, I worked on it in the morning and then I’d weave in the afternoon. It was a rather hard time for us financially. My wife had to teach a lot and help us keep going.

IP: Why did you decide to write that book?

Peter Collingwood: I had been teaching in London art schools and I began seeing things appear in magazines that I know I had taught people. I began to get a bit uppish, thinking that I should get credit for these things because I had thought of them first. Also, there was no big book on rug weaving, and the more I researched the subject, the more I realized what was involved in multi-shaft rug weaving and that not much of it had been written down. Once I started writing the rug book I also realized that there were many gaps in my knowledge. Up until then I had just woven 2/2 twills, so that when I did the chapter on twills, I had to make many samples just to find out how other twills worked. And when I did the chapter on corduroy I found that there were many different things you could do with the technique. I do think that many people don’t realize how much original stuff is in this book. Today people think that shaft-switching has always existed. I suppose, though, that in 100 year’s time, it really doesn’t matter who thought of these things, but I do like to think up things. I like sitting at the loom with a warp and seeing what I can do with it.

IP: It seems like it would be easy for you not to want to share what you’ve worked so hard to learn.

Peter Collingwood: Well, I always want people to like me, and people like you if you tell them things! The book has paid off, though, hasn’t it?

IP: Would you say that The Techniques of Rug Weaving is what made you known?

Peter Collingwood: Yes, I think so, much more so than my weaving. It was that book that got people wanting me to teach in America. Another reason I wrote the book—and I’m just remembering this now—was so that I wouldn’t have to teach anymore. I thought that if I got the whole bloody thing down between two covers, there’d be no need to teach anymore. Then, of course, some people just can’t learn from books, or often people think that you’ve kept a few things up your sleeve, and that if you actually teach them personally, they’ll learn a bit more. So as a means of stopping my teaching, the book was a complete failure. For me, classification is important. All the books I’ve written have begun with a compilation of great bundle of knowledge which I try to clarify. It pleases me to put order into things, and it’s something that I think I can do. I suppose that this comes from my medical training which encouraged me to think in an orderly way.

IP: Tell me about you latest book, The Maker’s Hand.

Peter Collingwood: This is a book whose idea didn’t come from me. It was either Ib Bellew’s or Ann Sutton’s idea. Ib told me that I’d done all these books which had been such a hard grind work, and that now I should do a nice easy book. “You’ve got all these textiles,” he said, “all you have to do is write a few sentences and scribble a few diagrams, and there you are.” I suppose it was easier than my earlier books, but it wasn’t easy. I wanted to say something interesting about each textile. I wanted to arrange the pieces according to a textile classification and then pages needed to alternate between black and white and color, and it was very difficult to marry these two concepts. I wanted to diagram each piece, and many of the structures I had not tried to diagram before. I found this part of the process quite difficult and time-consuming.

IP: What’s coming next?

Peter Collingwood: At the moment, I am very interested in the technique of ply-splitting, and I have collected over 50 camel girths from Rajasthan, India, almost the only place in the world where this method is used. This could be the subject of another book—perhaps another one like the sprang book, which people buy then never seem to use!

IP: Any advice?

Peter Collingwood: When I left Ethel Mairet, she sent me a letter saying, “Be as self-critical as I am in my workshop, then you may get somewhere.” I have tried to follow that piece of advice, though it is hard to really be critical about a new piece you have put a lot of thought and time into. Over my macrogauze loom there is an Eastern saying, “The simple only reappears after the complex is exhausted.” I have found this very true, both in weaving and when writing about complicated structures.

To learn more about Peter Collingwood, visit his website at: www.petercollingwood.co.uk